New financing instruments have been invented since the time of the Phoenicians and the Médicis. The modern corporation was developed by English and Dutch trading companies in the 1600s, and some believe the genesis goes back as far as the 1300s in France. With that modern concept of multiple owners of a single entity, it drove the early advent of banking as an organized business as well.

In the 1970s, the junk bond was created, which drove leveraged buyouts and the likes of Michael Milken, one of the leaders of the new Wild West of lending, a world that thrives even today for those seeking to leverage their businesses in the name of growth.

But earlier this year, the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank resulted in a painful tightening in the traditional credit markets, as fear spread about the ability of regional banks to survive the sudden spike that has quintupled interest rates just since the end of the pandemic, when the Fed undertook their late response to rampant inflation by hiking rates.

Private Credit. Fluid and robust credit flowing in the markets is critical to the underpinnings of a growing economy, yet it appears that tightened credit standards have not led to the slowdown everyone expected. This is due in no small part to yet another new instrument that made its debut just a few years ago: private credit. In 2011, in the waning days of the Great Recession, private credit growth accounted for just 4.4% of all outstanding debt, and today, it has ballooned to a growth rate of 277% of all debt outstanding.

This shift is accelerating a trend more than a decade in the making. Hedge funds, private-equity funds and other alternative-investment firms have been siphoning away money and talent from banks since a regulatory crackdown after the 2008-09 financial crisis. Lately, many on Wall Street say the balance of power, and risk, has hit a tipping point.

The loans are expensive, but for many companies they are the only option. Next, private-credit firms are coming for the rest of the credit market, bankrolling asset-backed debt for real estate, consumer loans and infrastructure projects.

Private-equity firms use revenue from most of the loans to make leveraged buyouts, saddling the companies they acquire with expensive debt. Ultimately, more companies could end up under their control.

Private credit assets under management globally rose to about $1.5 trillion in 2022 from $726 billion in 2018. At the end of 2022, the biggest Wall Street names had grown their private credit portfolios dramatically.

- Apollo has $268 billion in private credit loans outstanding compared to a mere $75 billion in 2018.

- Ares and Blackstone, the next two largest players, are at $241 and $206 billion, respectively, as compared to $75 and $54 billion, respectively, in 2018.

The firms have money to spend from clients such as pensions, insurers and increasingly, individuals. Those investors piled in because returns were high compared with other debt investments in a low-yield world. Private lenders delivered average returns of 9% over the past decade on loans made mostly to midsize businesses, according to various data providers.

While big funds have gotten bigger, the field of private credit is also getting broader, including traditional investment companies and alternative-asset managers. Some believe investing in private credit is still in its infancy, with some analysts suggesting that it will be a trillion-dollar end market eventually, and the only question will be how rapidly it grows.

Two-Edged Sword. And like many other financial instruments, private credit is a two-edged sword. Some analysts are concerned about private credit taking over the loan market. The concern is that the shift has concentrated a larger segment of economic activity into the hands of a fairly small number of large, opaque asset managers, and a lack of visibility will make it difficult to see where risk bubbles may be building.

Regulators, concerned that so much money is going behind closed doors, are rushing to catch up with new rules for private fund managers and their dealings with the insurance industry.

But over time, private credit will expand to smaller loans, and will undoubtedly become a financing instrument for companies in the construction aggregates industry.

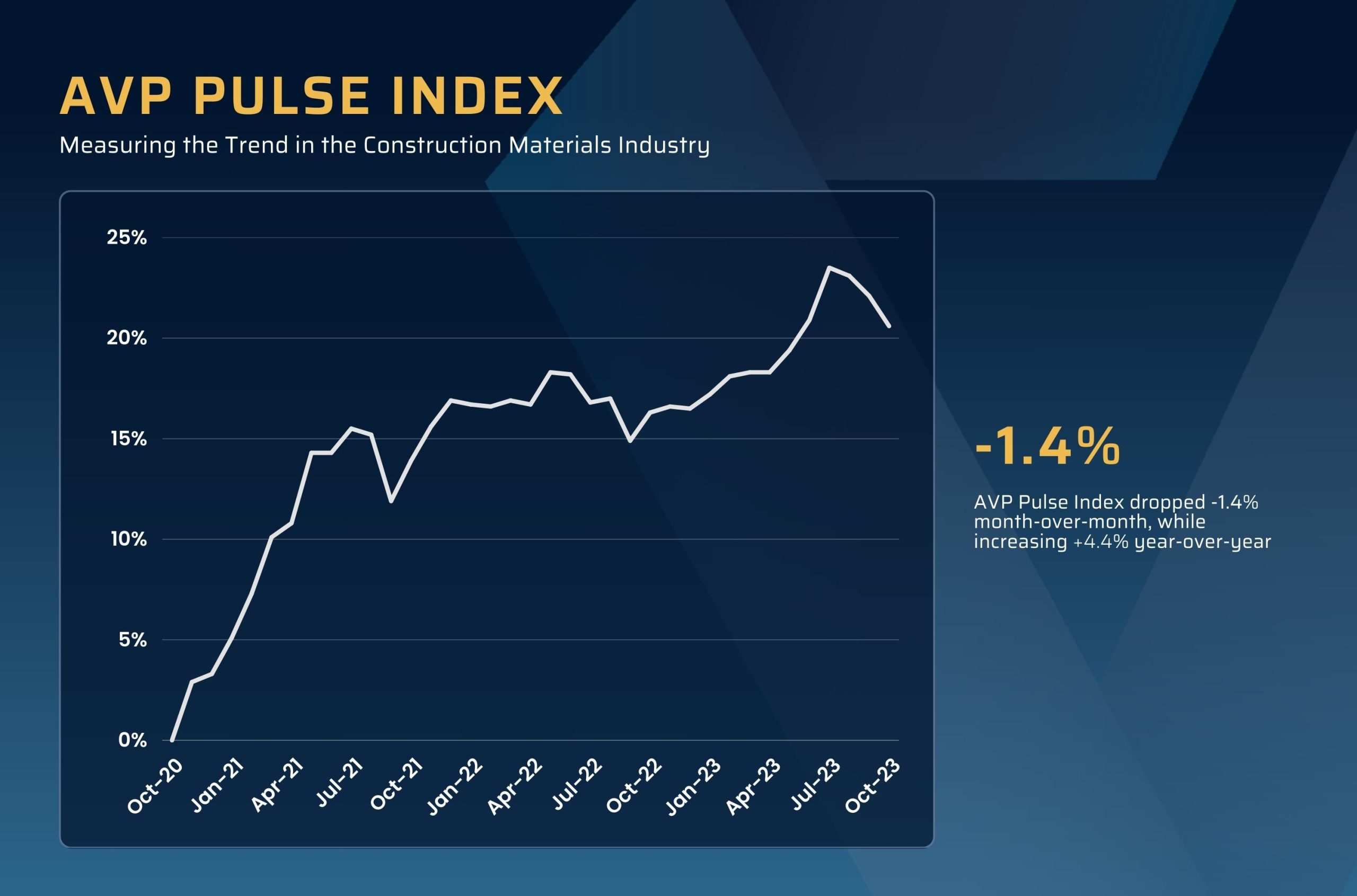

AVP Pulse Index. The previously flattened curve of the Index turned down for the second month, indicating the see-sawing of various economic indicators as the economy shows strength in certain areas, and softening in others, which we consider to be temporary. And the news is mixed, with enough of a slippage in various confidence indexes, yet some increases in others. Dodge Data Momentum Index and Construction Spending were up, but the housing indexes were down for the month. The continued optimism among investors in the publicly traded construction materials companies has stock prices elevated which helps steady the AVP Pulse Index algorithm. There is no doubt that a flat new home construction market is being more than offset by IIJA projects flowing through the economy. Once again, NO RECESSION in sight.

Pierre G. Villere serves as president and senior managing partner of Allen-Villere Partners, an investment banking firm with a national practice in the construction materials industry that specializes in mergers and acquisitions. He has a career spanning almost five decades, and volunteers his time to educate the industry as a regular columnist in publications and through presentations at numerous industry events. Contact Pierre via email at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @allenvillere.