Does Your 2024 Budget Set You Up For Failure?

By Barry Hudson and Steve Franklin

In the first of this two-part series, which appeared last month, the authors stated the challenge and offered initial advice. In part two, they identify solutions. – Ed.

When thinking about the aggregates industry, and how fixated some people are with volume, as opposed to profit, a television advertisement from the early 1980s always springs to mind.

It goes like this:

A farmer in his 70s is leaning on his pickup, parked on the side of a country road and the pickup is stacked high with pumpkins. Beside the pickup is a sign – Pumpkins $1.00. A young, keen financial planner pulls his car up behind the pickup and the young man gets out of his car and approaches the farmer selling the pumpkins. “How is business?” asks the financial planner. “Yeah, really busy, selling lots,” replies the farmer. “So you are making plenty of money then?” enquires the financial planner. “Actually, no I am not,” replies the farmer. “Well then, let me help you out,” says the financial planner. “How much do you buy your pumpkins for?” The farmer answers “a dollar.” “Ok, how much do you sell your pumpkins for?” asks the planner. The farmer replies “a dollar.” The planner thinks a little bit and says, “I think you need a bigger truck.”

For so many in our industry, more is more. If we actually forecast and plan correctly, the adage “less is more” can be very true. Especially measuring the success of your business by profitability – EVA (Economic Value Add).

How do we ensure we don’t destroy the long-term value in our business, especially by making short-term decisions that may have a negative outcome many years ahead. In essence, this seems pretty simple. Forecast what you are going to sell, and then have the operations people make those products.

Be honest. How many of your operations have well-structured communications with their commercial counterparts? How many of the operations people, and commercial people have the data to make informed decisions?

Sales Forecasting

What exactly is a sales forecast? Is it when your sales team gets together and tells production what they have sold? Is it an arbitrary value that was determined last October in the budgeting process?

Do you have any mechanisms in place to look at the long-term, or even short-term profitability of a sales forecast, or accepting an order? Take for example, accepting an order for a high-value single-sized aggregate. You have established that the production cost of that one aggregate is say $5.00 per ton. The sales order comes through for 30,000 tons of this high value aggregate, and sales celebrates the $25.00 price tag they got for the bid. But, the yield of that high value aggregate in production is only 10%.

We are not saying in this example “don’t make the sale” – but, please do not fall for the common mistake of – I made a $750,000 sale, production costs were $5.00 x 30,000 tons = $150,000, therefore I made the company $600,000.

You have achieved $750,000 of revenue. If you were going to try and look at each sale in isolation, you would have to say that the 30,000 tons of product you sold needed 10 times that tonnage to produce (remember the yield of the high value aggregate was only 10%) so in simplistic terms, there were 300,000 tons of production costs that went into making that particular order. Perhaps a better way of stating the outcome of the sale would be:

“I sold 30,000 tons of high-grade aggregate for $750,000, it cost us $1.5 million to make the product, but we have 270,000 tons of other aggregates sitting in inventory that have half of their production costs covered.”

Of course, other aggregates that were produced as this high value aggregate was manufactured will be sold, and yes, you cannot look at one transaction in isolation, but, with a group of products, over a period of time, this becomes important.

There are many clichés in aggregates – “sell what you make, don’t make what you sell,” or, “sell the curve.” What is being preached with these clichés is that pit balance, or balanced inventory is one of the keys to profitability, long- and short-term.

Where Does This Problem Start? And How Do You Fix It?

As a sales team in aggregates, do you take these things into consideration when forecasting? Do you have the knowledge and the tools to tell yourself to say no to that order – quite simply, accepting the order will be loss making over time?

Of course there are pressures to achieve monthly sales volumes and targets – but breaking profitability down into these small periods of time often leads to negative long term decisions.

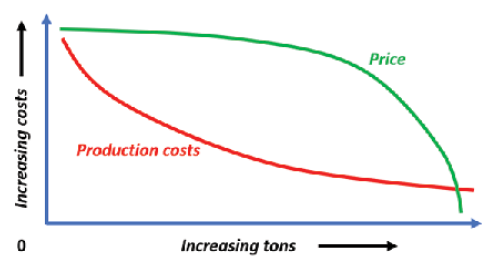

The following graphs indicate different profit scenarios during a year.

In this first graphic, we see the total Product Cost in red (both fixed and variable), and the Sales Price in green. This graph, and the following graph are not chronological, but cumulative lines as tons of both production and sales increase. In this example, we see that the price does not intersect the cost line until near the end of the number of tons produced. Whenever the price line crosses the cost line, all products are being sold at a loss.

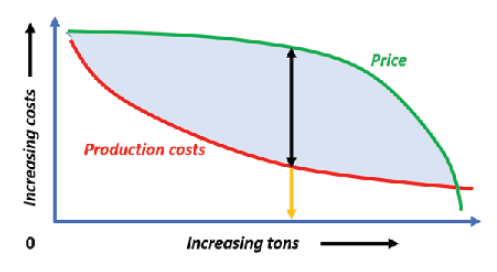

Carrying on to the same graph below, we can see that the shaded light blue area represents the margin or profit for that product, for a given tons produced AND sold.

And the black arrow in the light blue shaded area shows the tonnage produced AND sold that gives the greatest profit for that particular product. The blue shaded area is the profit for that site. Not all aggregates sites will have the price line intersect the cost line.

Of course, these linear graphs do not reflect chronological reality. However, they are critical to establishing where in your production and sales mix, is the right volume of production and sales to be the most profitable. Remember, we are a long-term business, and we need to be trying to achieve maximum profit for every ton extracted.

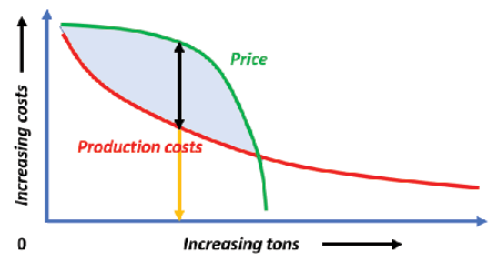

In the example above, we sell nearly everything we make. However, if we were to say sell only half of what we make, the result would look like this:

Of course, there are many products in a quarry – in most cases, too many. Each has their individual fingerprint or graph. Each is vitally important. Of course, the optimal product/sales tonnage will be different for each product. The key is to combine all the products and understand the envelope that makes your pit or quarry the most profitable.

And it all starts with sales. Depending on the price, and the projected profitability, should sales be picking up that order, or instead, should they be saying “No!” Our experience is that our sales and commercial people are not given the training or the tools to be able to fully comprehend, and therefore make the best decision in most circumstances.

Your Budget – Is It Doable?

A great place to start looking at your profitability is your very first sales forecast for the year. Yes, your budget. How many budgets are prepared with pit balance in mind? This after all, is your target, what you are measured against, what drives your performance metrics. Does your budget actually make sense? Are the splits of your products, or your product yields, what the production unit can deliver?

One common mistake when budgeting aggregates is that the split of sales by product does not match the split of products by production. What happens then is a common mistake.

Finance will add up the total revenue from the sales budget/forecast, and subtract away the production costs for that number of tons. Bang. Straight away, there is an imbalance. And even though there may be some adjustments to correct for this in the beginning, experience shows us it is never enough. If this is the case, you are fighting a losing battle from day one, and only a pick-up in sales volume and/or price will bring you home at the end of the year.

Supply Chain Management Thought Process

As Steve Franklin, CEO of Eltirus.com, explained, the pit is the warehouse, what products are coming when?

You could consider that your quarry is actually a warehouse. A warehouse that nature sorted and stacked, but a warehouse all the same. We just have to drill and blast the material out, dig it out and haul it ready for processing, but the concept still holds.

What would you think of a warehouse manager who did not know where things were located in their warehouse? Can you imagine the bedlam as items were randomly selected and moved to find the “useful ones”?

In reality, much quarry planning is of a similar nature – bedlam, particularly when you start to factor in overburden removal requirements (often a key cost driver).

The simplicity of it is as follows:

- You work out what rock types are where in the quarry.

- You work out what can be made from each rock type and what the resultant yield is.

- You determine how many hours in the year you can operate (based on licence, site configuration and so forth).

- You determine the production capacity of your loading tools and haulage fleet.

- You use a scheduling tool to work out what needs to be moved from where and when to meet the sales plan.

- If the scheduling model says you can’t meet the sales requirement, you look at a different scenario and re-run the schedule.

Clearly, the “simplicity of it” may be a gross oversimplification and there can be quite some factors to think through. However, this is an exercise well practiced in the mining industry for at least the last twenty years.

We have had great success adopting a class-leading mining scheduling engine for use in quarries to carry out exactly the sort of analysis noted above.

Using Deswik. Sched software enables our clients to determine (in conjunction with sales) what material is available, in what quantities and when. It also helps them understand how much overburden needs to be moved and when this needs to happen. Different ideas can be run as separate scenarios to give both operations and sales managers clear forecasts on what is possible. By way of example, one client found (using this approach) that they could satisfy the requirements of a major sales contract for a period of two years but would fail in year three without a significant overburden stripping campaign.

Knowing this, they were able to factor this requirement into the price and the operational budget. The takeaways from this were that operations knew what they had to do and that they needed to find dumping space, management had a heads up on a major capital cost ahead of time and sales received the word that they needed to do everything they could to find a major fill project to sell the overburden into to reduce the dumping cost. This was a win-win for all concerned.

Nature hasn’t always been the most organised warehouse manager – give her a hand by applying some scheduling technology to help sort it out.

Barry Hudson is the co-founder of Price Bee, www.price-bee.com, a culmination of experience and ideas forged together over five years to become a powerful tool to streamline your sales process and increase revenues in the construction materials industry. He can be contacted at [email protected]. Eltirus is a global consulting company that works to help the construction materials, cement and industrial minerals industries better understand what’s in the ground, how to extract it sustainably and how to ensure compliance to plan and statutory requirements. Contact Steve Franklin at [email protected].