By Joe McGuire

This Rock Products special report, authored by safety consultant Joseph McGuire, was written to refute the findings in a recently released study, “Evaluation of Silicosis, Asthma and COPD Among Sand and Gravel, and Stone Surface Mine Workers.” – Ed.

Exposure to hazardous contaminants, including respirable silica dust, is a risk that is acknowledged and addressed within the stone, sand, and gravel industry (SSG). Routinely, mine operations consult the hierarchy of controls to identify ways to eliminate, substitute, engineer out, or change work processes to reduce potential exposure. A last resort is the use of respiratory protection in some work areas. Although just lower exposures are too much, a recent article titled “Evaluation of Silicosis, Asthma and COPD Among Sand and Gravel and Stone Surface Mine Workers” (JOEM 2022) might lead readers to believe workers in SSG mines suffer from high incidents of silicosis, asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

This paper is being written to clarify information presented in that article. This will be accomplished by:

- Providing a brief overview of Michigan’s and the Mines Safety and Health Administration’s (MSHA) rules and regulations written to protect mine workers from potential health issues caused by fugitive and respirable (PM10 and PM2.5) dust. This includes silica dust from SSG mining operations.

- Explaining the basic differences between sand and gravel and limestone mining as compared to granite mining described in the references used to support this research.

- Pointing out that many of the sources, used to support their premise, are dated and not comparable to Michigan’s sand and gravel mining industry.

- Showing how their own results indicate there is little or no correlation between silicosis, asthma or COPD and those who work in Michigan’s sand and gravel and stone mines.

Control of Mine Site Respirable Dust

Michigan defines fugitive dust under R 336.1106(k) of the Michigan Air Pollution Control Rules as “particulate matter which is generated from indoor processes which is emitted into the outer air…or outer air from outdoor processes, activities, or operations…” The most common regulated forms of particulate matter are known as PM10 (10 microns or less in diameter) and PM2.5 (2.5 microns or less in diameter). PM10 are also called respirable dust particles.

Mining operations are identified in Section 324.5524(1-2) which mandates fugitive dust programs and opacity limits for facilities. “The Air Quality Division (AQD) of the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) may…require a fugitive dust program from a facility if it processes, uses, stores, transports, or conveys bulk materials from a highly emitting and…is a listed activity in Michigan R 336.1372”. In addition, “The U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) requires stone, sand and gravel mine operators to control and manage worker exposure to silica dust and Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS)”.

In Michigan, most sand is mined by excavating deposits that are near the surface or below the water using dredge operations. After sand is mined, it is washed, sorted by particle size, and stored until it is transported off-site for construction projects. Regulations and best management practices are in place in Michigan to protect workers, as well as the public, from fugitive and respirable dust created during the mining, processing, and transport of sand.

The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy suggests the following secondary and engineering dust control measures to comply with MSHA or DEQ requirements:

- When possible, store materials inside of a building.

- Have customers use tarps to cover loads.

- When possible, use covered trucks and rail cars.

- Apply water or other dust suppressing spray on piles, equipment and roads.

- Use mechanical control devices such baghouse or cyclones.

These measures help reduce emissions of silica dust into the ambient air and limit exposure to workers and the public. Michigan stone, sand and gravel producers, take steps to ensure the health and welfare of their workers by monitoring and controlling all dust emissions as required by the EGLE air quality permits and MSHA Silica Enforcement Initiative.

Sand and Gravel and Stone Mining Compared to Silica and Industrial Sand Mining

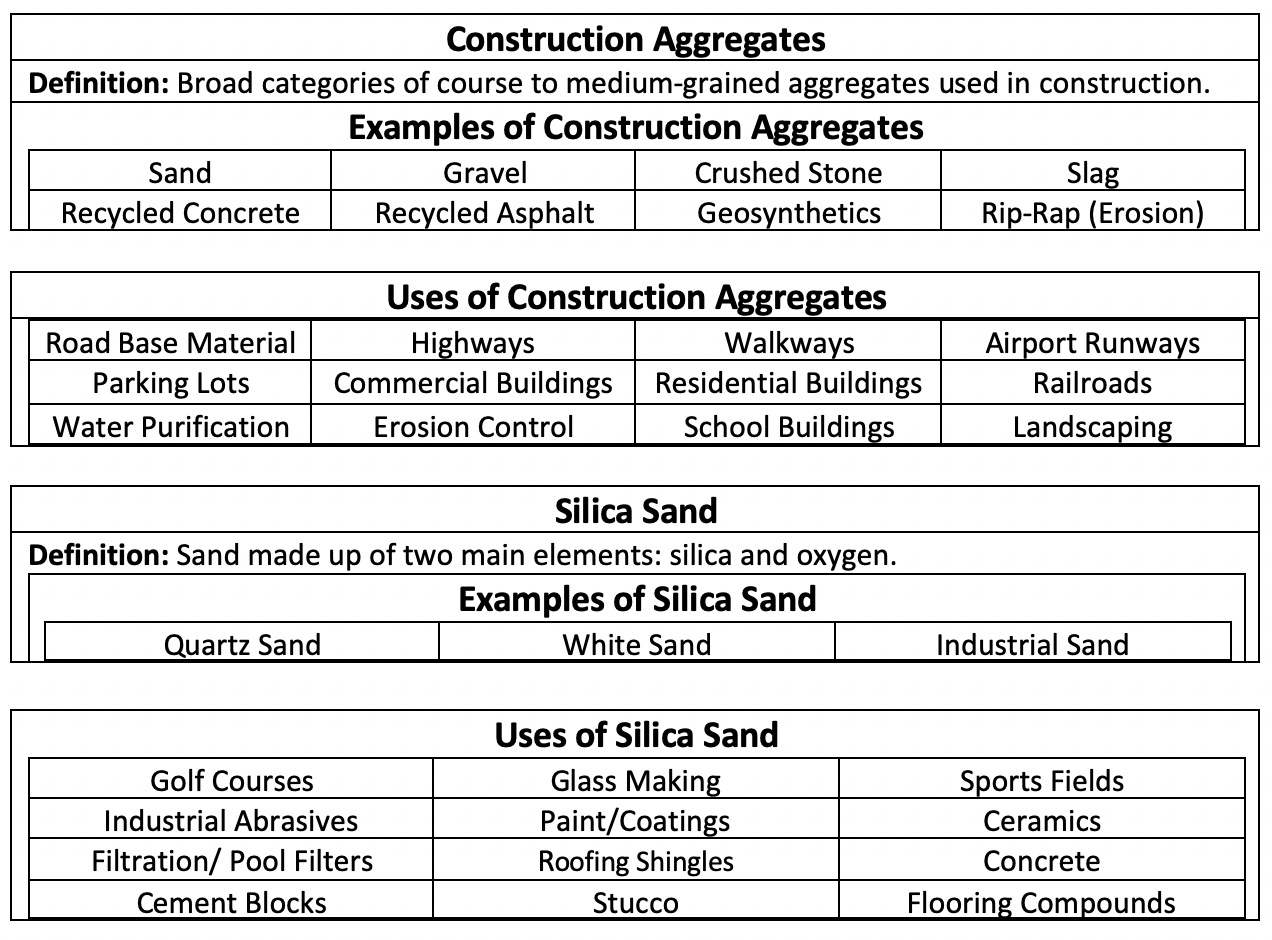

As background, we should first clarify the difference between “sand and gravel and stone” production, which was purported to be the basis of this article, as compared to “industrial minerals or silica sand.

Sand and gravel are mined from dry bank excavations using power shovels, draglines or front-end loaders or from water by dredges. After removal, the materials may be used, without processing, for fill, bedding, subbase, and base course. Or, the sand and gravel may be transported to a processing plant which, using a combination of wash/screen plants or classifiers, size the aggregates for final use. Companies may also use a crusher to reduce oversized material for use on construction projects. Limestone and other hard rock is mined by drilling and blasting, followed by crushing and screening to produce the sizes and specifications desired by customers.

Silica sand deposits are most commonly surface-mined in open pit operations, but dredging and underground mining may also occur. After extraction, it is processed to increase the silica content by reducing impurities. It is then dried and screened to produce the white, low iron silica sand which is in high demand. This material is produced by dry grinding in ceramic lined mills using flint pebbles or porcelain balls. Silica flours are produced using mills to grind rounded silica sands into a finer particle size.

The end uses of sand, gravel and stone versus silica, the processes used to produce them and the emissions generated by them are different.

Source Review

The author of this article states “The risk of silicosis in stone quarry sheds(1,2) as well in the milling/bagging of silica(3) has been documented. There have been case reports from state surveillance systems on the occurrence of silicosis among surface sand and gravel miners (4–7). Individuals exposed to silica during mining operations are at risk not only for silicosis (8) but also for COPD (9). In addition, miners are also potentially at risk of developing work-related asthma (WRA) from exposure to diesel fumes and other workplace allergens and irritants (10). Approximately 43% of all miners in the United States are surface sand and gravel or stone miners”.

Several decades ago, “Quarry sheds” were buildings in granite mines where materials were cut and polished by workers. The data described in these 60-year-old studies were based on Vermont and Georgia Granite Mines at a time when dust, emitted inside of these buildings, was uncontrolled.

Controlled dust emissions from today’s open pit sand, gravel and stone mining and processing operations cannot be compared to those generated in “quarry sheds” used many years ago in granite mines. There are no “quarry sheds” used in Michigan’s sand, gravel and stone industry and the implication that there is a correlation between silicosis, asthma or COPD and sand and gravel miners in Michigan, based on this old research, is a “stretch” at best.

Likewise, the study compares exposure to silicosis from sand milling and bagging operations to Michigan sand, gravel and stone processing. The cite states “Silica flour is used industrially as an abrasive cleaner and as an inert filler.2 Silica flour is found in toothpaste, scouring powder, and metal polish. It is an extender in paint, a wood filler, and a component in road surfacing mixtures. It is also used in some foundry processes….Many cases of silicosis have been reported in sandblasters”. Since Michigan sand, gravel and stone operations provide constructions materials and do not conduct “milling and bagging operations”, which fine grind silica sand for these and similar uses, comparison again is a “stretch”.

State surveillance systems track the occurrence of silicosis related to silica exposure from sand and gravel mining. Yet citations used in this study were based on “generally older men who began work before 1960 and had worked for 15 years or more in potteries, construction, foundries, or sand mines…256 cases of silicosis that were initially ascertained in 1993. 188 (73%) were associated with silica exposure in manufacturing industries (e.g., foundries; stone, clay, glass, and concrete manufacturers; and industrial and commercial machinery manufacture). Overall, 42 (16%) cases were associated with silica exposure from sandblasting operations”. In addition, they indicate the “Traditional industries and activities in which silica exposures occur include foundries, sandblasting, mining, tunneling, ceramic products manufacturing, and construction. Emerging industries with silica exposure include manufacturing and installation of engineered stone countertops, oil and gas hydraulic fracturing, and highway repair”. “Sand mines” or type of “mining” are not defined in these documents.

This research also fails to show there is a correlation to working in sand and gravel mines and COPD and asthma from diesel engine exhaust emissions. As indicated in the authors citation #12, “Miners are highly exposed to diesel exhaust emissions from powered equipment. Although biologically plausible, there is little evidence based on quantitative exposure assessment, that long-term diesel exposure increases risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)”.

Results or Findings

Based on the data generated by the individuals in this study, the authors found:

- “No individual had radiographic changes consistent with silicosis or asbestosis”.(Pg. 264)

- “No individual had definite work-related asthma”. (Pg. 264)

- “Six individuals had asbestos-related pleural changes”. (Pg. 264) “Three of the six workers with pleural changes consistent with asbestos exposure worked in the UP, a fourth worked in the Quebec asbestos mining region before moving to Michigan. Asbestos is a known contaminant of the iron and soil overload that has been mined in the UP. Complete work histories were not known for the two individuals with pleural changes from the northern Lower Peninsula”. (Pg. 268)

- “No cases of silicosis were identified in this study of Michigan surface sand and gravel mine workers”. (Pg. 266)

- “As compared to the working population in Michigan (11) the surface sand and gravel mine workers reported less COPD (Table 6). Consistent with this finding, surface sand and gravel mine workers had a lower prevalence of ever smoking cigarettes compared to the working population in Michigan”. (Pg. 266)

- “We assessed the various outcomes with subgroups based on occupation categories of miner, maintenance worker, welder, truck driver, and contractor. These occupation categories were used as surrogates of potential exposure to silica with miners, maintenance workers and welders considered to have the highest potential for exposure, truck drivers less and contractors the lowest. No significant association between COPD and latency was found by the occupation categories of miners, maintenance workers and welders truck drivers, or contractors. The results of these analyses are not shown in this paper”. (Pg. 266)

- “As compared to the working population in Michigan (11) surface sand and gravel workers reported ever having asthma less frequently”. (Pg. 266)

- “The percentage of miners with possible work-related asthma is similar to the 12% of co-workers reported in facilities, generally factories, inspected by MI OSHA during follow up inspections of index cases of work-related asthma”. (Pg. 266)

- Fourteen of the 26 individuals with abnormal results had decreased FVC on spirometry, a potential indication of restrictive disease (i.e., silicosis). However, for thirteen of the 14 where BMI was known (one unknown) all were either overweight (n ¼ 6) or obese (n ¼ 7). Excess weight is a common cause for a decreased FVC in the absence of lung disease. Lung volumes measured by plethysmography would be needed to determine if these individuals truly had restrictive disease. Such testing was beyond the scope of this project.

These points, taken directly from the study, would seem to indicate working is SSG mines in Michigan poses no unusual exposure to health issues. This is not to say, workers will not be exposed to silica dust in sand and gravel mining operations, but companies routinely take steps to assess exposure to hazardous contaminants and determine methods to reduce these exposure sources on the job.

Perhaps, the first and seconds sentences of the Discussion best summarize the findings of this study. The author states:

- “No cases of silicosis were identified in this study of Michigan surface sand and gravel mine workers. The absence of cases of silicosis in our study was unexpected given the documented risk of silicosis in stone quarry sheds (1,2) and in the milling/bagging of silica (3), case reports from state surveillance systems on the occurrence of silicosis among surface sand and gravel miners (4–6) and the potential for silica exposure in surface sand and gravel mines”

It appears the authors fully expected, and set out to prove, there are higher incidents of silicosis, asthma and COPD among workers in Michigan’s SSG mining industry. Perhaps their findings would have been more meaningful had they taken time to learn about the construction aggregates industry and not tried to paint all types of mining with the same broad brush. Had they taken time to learn that “stone quarry sheds” and “milling and bagging operations” in granite mines and “silica flour” operations are very different from typical construction sand and gravel and stone operations, they might have come away with different findings.

Companies in the mining industry are always open to learning more about issues which might affect the health and safety their workers. Unfortunately, this research does little to enhance the body of knowledge focused on protecting the health and safety of miners.

Joseph McGuire, Ph.D. is an independent safety and health consultant ([email protected]).